THE REVOLUTION THAT ATE ITSELF: JAPAN'S RADICAL STUDENTS

THE REVOLUTION THAT ATE ITSELF: JAPAN'S RADICAL STUDENTS (PART 1)

(11,000 words)

Japan's student protest movement around 1970 made American anti-war demonstrations look like picnics in the park.

Part 1 Part 2

1. The Snow Murderer I. Bombs and Busts

2. Solution = Revolution II. There's Revolution in the Air

3. University Blues III. An Offshoot of an Offshoot of an Offshoot

4. The Rules of the Game IV. The Merger

5. The Tower V. Throwing Out the Garbage

6. Time Waits for No One VI. The Snow Murders

VII. Now We Are Five.....

VIII. .....Against a Thousand

IX. The Dangling Threads

X. Dreams of '68

===================================================================

NOTE: A SLIGHTLY DIFFERENT VERSION OF THE REVOLUTION THAT ATE ITSELF: JAPAN'S RADICAL STUDENTS FIRST APPEARED ON MY PREVIOUS WEBSITE BACK IN 2018

=============================================================

PART 1

1. THE SNOW MURDERER

One look at Hiroko Nagata and you know there's trouble.

She was not your average murderer. When the Japanese police finally caught her in February 1972 she'd participated in 14 homicides. All but two of her victims - including a heavily pregnant woman - were fellow members of the terrorist group Rengo Sekigun (連合赤軍), "the United Red Army" (URA). Its revolutionary agenda was wildly ambitious for a group with barely 30 members sleeping on the floor of a single-stove alpine cabin.

The Japanese media branded Hiroko Nagata a she-devil. In the aftermath of "the snow murders" every criminologist, psychologist and talking head in the land dissected her psyche. She'd led the URA alongside her lover, the glib, dictatorial Tsuneo Mori. During police interrogation both were secretive about their relationship. They had every right to be.

This is the story of how the tumultuous student protest movement in the 1960's-early 1970's turned Japanese universities and cities into war zones. We'll see how the student radicals' attempts to foment a class war:

* alienated the very people they claimed to champion,

* unwittingly started a chain of events leading to one of the movement's main group's - the United Red Army's - self-destructive homicides and

* how a snowball effect led to the URA's final traumatic shoot-out with 1,000 police.

We'll also see how this group was ultimately, if indirectly, responsible for a brutal terrorist outrage which rocked the Middle East.

2. SOLUTION = REVOLUTION

Japan's post-1945 generation grew up in a vastly different society from what their parents knew. Democracy filled the air. The emperor was a living god no more. The old militaristic ethos was dead. And at long last the Japanese parliament had an actual political spectrum. In fact - who would have imagined it? - some parliamentarians even belonged to the Japan Communist Party, the JCP.

Few Japanese aspired to live in a Soviet-style dictatorship, but only the communists had resisted Japan's rampant militarism. For that they'd rotted in military prisons. When the 2nd World War ended thousands of half-starved JCP comrades emerged from their dungeons, blinking in the sunlight and scratching their lice.

They saw the pendulum had swung and they got straight to work. And as Japan's dispirited troops returned to their devastated homeland, these newly freed communists rammed home the message: Why didn't you all listen to us when you had the chance?

The prewar leadership's ideas were now discredited. The Left had the moral high ground and took the upper hand. America's supremo in Occupied Japan, General Douglas MacArthur, was no friend of the Lefties, but he was tasked with turning Japan into a warts-and-all democracy. So the communists were free to organize and evangelize.

Waving the red flag in factories was considered a good thing, but universities became the JCP's happy hunting grounds. Today's students are tomorrow's leaders, the communists declared, and the young have fertile minds. Universities - dilapidated and still bomb damaged - hummed with leftist activity. Students with vivid memories of the war flocked to on-campus Marxist study groups working towards a better world. And they learned to sing the communist anthem The Internationale in Japanese.

The JCP was there every step of the way. Wasting no time, Communist agents cultivated the new All-Japan Federation of Student Self-Governing Associations. Its abbreviated Japanese name was Zengakuren. And young Marxists soon dominated its leadership.

The Zengakuren-JCP bond tightened as the Cold War intensified. It had to. Angered by the government's crackdowns on the Communist Menace, 20,000 members stormed the emperor's palace, initiating the ultra-violent 1952 protest campaign. Zengakuren used molotov-cocktails and threw ammonia into the riot cops' faces.

But by 1958 doctrinal differences produced cracks in the JCP-Zengakuren alliance. The students severed the bond. The old-school JCP communists and the university firebrands became bitter enemies.

Things were really coming to a head by the 1960's. Japan's booming economy needed university graduates. But how were students supposed to gain meaningful educations in cramped, dilapidated lecture halls, standing-room-only libraries and ramshackle labs?

Why were Japanese universities run by Dean Kickback and Professor Under-The-Table?

Why were lectures delivered by Associate Professor Working-On-Ways-To-Improve-My-Teaching-Would-Just-Be-A-Waste-Of-Precious-Milliseconds?

Q: Why do Japanese professors hold teaching in such contempt?

A: Because it interferes with getting published and waging faculty power struggles.

The undergraduates' frustration reached boiling point.

Their frustration wasn't merely about abysmal campus infrastructure, professorial indifference, exorbitant tuition fees, administrative inertia and built-in corruption. Japan's servile attitude to Washington during the recent security treaty negotiations was on everyone's mind. The prime minister's apparent eagerness to negotiate away Japan's rights as a sovereign nation enraged both leftists and nationalists. In 1960 their fury took a dramatic turn.

Zengakuren students and their allies stormed the parliament that June. One of the 5,000 riot police killed a 22-year-old female student, Zengakuren's first martyr. 300,000 protesters then surrounded the parliament building.

Now came a momentous shift. Zengakuren's radicals had long expressed outrage that their compatriots tolerated such political leadership. Now they asked how people could tolerate such a corrupt political system. Every radical ("rad") agreed: revolution was the only solution. But then the movement splintered into a bewildering forest of factions. Everybody proclaimed the need for revolution. The big question was What kind of revolution? From the 1960's into the early 1970's this question fueled countless impassioned debates. And lots of violence.

3. UNIVERSITY BLUES

The spring of 1969.

A year earlier the streets of Paris heaved with students and workers, teachers and truckers, plumbers and poets waving banners and chanting revolutionary slogans. 11,000,000 workers went on strike. France was on its knees. But then the flame of the May '68 Revolution spluttered. In June French conservatives won a solid electoral mandate. When the dust settled it was like May had never happened.

There were obvious lessons in this, but they bounced off the heads of Japan's radical students. Meanwhile, their campuses remained woefully unhappy, overcrowded institutions whose professors remained uncontaminated by concern for their students.

With a few praiseworthy exceptions a typical Japanese university was administered by self-serving timewasters and hack professors.

Desperately needed student housing was still being demolished and the vacant blocks sold to real estate pirates. But ... what differentiated 1960 from 1969 were (a) the Vietnam War and (b) all those left-wing factions.

The May '68 demonstrators protested the Vietnam War - as if Washington gave a hoot what the Frenchies thought - but they also protested underfunded universities, outdated teaching methods, government arrogance and bureaucratic sloth. This resonated with Japan's students. Even so, France was a world away from Asia. Uncle Sam's latest war was on Japan's doorstep. U.S. air and naval units routinely attacked North Vietnam from bases in Japan and Okinawa.

Nationwide protests condemned their craven government's willingness to make Japan a cog in America's war machine. Japanese Leftists were divided on everything except Vietnam. On that, at least, they stood firmly united.

Some preached worldwide revolution. Some wanted to smash Japan's alliance with America (like Hiroko Nagata's group, emerging in '69). Or smash capitalism. Or smash the whole consumer culture.

The Revolution starts here

Visit any major Japanese campus in 1969 and you couldn't miss the sprawling spectrum of opinions - except on the Vietnam issue - everywhere you looked. It would be a jungle of political consciousness groups, revolutionary brigades, revolutionary fronts, revolutionary corps, revolutionary armies, revolutionary alliances, revolutionary councils, solidarity committees and action groups. Everyone was anti-this / pro-that. Everyone was an -ist or an -ite.

If the factions ever considered setting aside doctrinal differences for the benefit of a greater cause, they never acted on it. Quite the opposite. This brigade denounced that council as scum and capitalist stooges. This front scorned that alliance for being maggots and imperialist lackeys. This solidarity committee had utter contempt for the fascist cockroaches in that corps.

When they weren't demonstrating against the Vietnam War, the U.S-Japan alliance, America's occupation of Okinawa or the constipated university system, on-campus radical leftist groups could usually be found drowning out rival factions' rallies with megaphones, erasing their rivals' graffiti and storming their offices. And much worse.

Political demonstration. What images come to mind?

21st-century demonstrations usually involve chants like:

WADDA WE WANT?

BLAH BLAH BLAH!

WHEN DO WE WANNIT?

NOW!!!

Whereas we imagine Japan - especially in bygone decades - as a constrained, polite and orderly society producing protest chants like:

WHAT DO WE RESPECTFULLY REQUEST?

BLAH BLAH BLAH!

WHEN DO WE RESPECTFULLY REQUEST IT?

AT THE APPROPRIATE JUNCTURE!!!

However, a typical Japanese student protest circa 1970 was like this 1-minute-and-16 -second video (SYND 1 6 71 TOKYO STUDENTS PROTEST...) (no sound):

and this (SYND 17-11-69 TOKYO STUDENTS ARMED WITH...) (also soundless):

https://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.youtube.com%2Fwatch%3Fv%3DUG_iH0Xyvts

Incidentally, the woman being arrested at the second video's 1 minute 27 second mark was Fusako (The Red Queen) Shigenobu. She'll figure prominently in part 2.

The inevitable questions here include:

(a) How did these student radicals ("rads") organize themselves?

(b) What was with all those helmets, towels and sticks?

(c) And those weird conga lines of protesters snaking through the streets?

(d) And how did the police - the riot police especially - deal with all this?

4. THE RULES OF THE GAME

White helmets, red helmets, white helmets with a red stripe, yellow helmets. Each signified something. Yellow helmeted protesters were with:

* the JCP (Communist Party). They had the numbers and the funding. But they avoided heavy violence, so lacked the obvious oomph of:

* the Kakumaru (Revolutionary Marxists): white helmets with a red stripe and big Z. They were the well-coordinated ex-partners of, and therefore the implacably bitter enemies of:

* the Marugakudo Chûkaku-ha (Marxist Student League Central Core Faction): white helmets with 中核 (Chûkaku "Central Core") emblazoned on them. This was the radical fringe's radical fringe. Chûkaku-ha aimed to make every other group look about as revolutionary as boiled cabbage and about as violent as the Vienna Boys' Choir. Or:

* the Shagakudo: red helmets with 社学同 (Socialist Student League) on the front. They adored the May '68 French protesters, and were respected for the sheer professionalism of their street barricades, if nothing else. Or the group we'll get to know very well in part 2:

* Sekigun-ha, or the Red Army Faction (red helmets emblazoned with 赤軍派 ["Red Army Faction"]). Originating around the western Japanese city of Osaka, it started bombing police stations and robbing banks. It perpetrated Japan's first airplane hijacking. Their mission? To "Escalate the Present Struggle into Armed Revolution". They claimed to be soldiers in a war to the death. And after a pivotal merger they became the United Red Army (URA)

These various groups all shared the same broad aims, but cooperation and coordination were the furthest things from their minds. Violent doctrinal conflicts among rival factions - uchigeba - were the norm.

Uchigeba (uchi meant "internal," geba was from the German word Gewalt, "violence") didn't manifest itself in mere shouting matches and erasing each others' graffiti. Like the Germanic tribes engulfing the Late Roman Empire, the various on-campus factions would just as soon fight each other as fight their common enemy (the cops). Convinced of their own ideological purity and every other faction's criminal betrayal of revolutionary ideals, each faction felt obliged to obliterate the others.

Uchigeba took various forms. Sometimes the violence was more ritualistic than actual. But just as often it meant brutal midnight "liberation raids" on rival groups' on-campus HQs. These involved brawls and arson. Radicals kidnapped "enemies of the Revolution" (other factions' members), slapped them around, applied a few cigarette burns and released them. But from 1970 the Kakumaru vs Chûkaku-ha enmity escalated into murderous torture. (More on this in Part 2.)

The police rarely intervened unless a university requested. They would rather see the "rads" claw at each others' throats on the campuses than have to deal with such violence on the streets.

Another schism in the -ism

Demonstrators protected themselves from teargas with towels soaked in water or lemon juice over their noses. They wielded gebabô ("violence sticks"). Some gebabô had iron tips or nails.

At street demonstrations they formed lines several protesters abreast and linked arms (making individual arrests more difficult). Chanting slogans, they zig-zagged towards the police lines.

Each "snake line" followed its line master, who led from the front. Like a traffic cop, he blew a whistle to direct the line. He set the rhythm and scouted for photographers and TV cameras, directing the line for optimum media exposure.

The hypnotic chanting and rhythmic movements mesmerized the protesters. As if to break the spell, the line master sounded a signal and the protesters immediately formed a phalanx. Everyone raised their gebabô and charged at the riot cops.

The police reaction varied. Sometimes they'd suddenly open their ranks and let the students through. The cops would then close ranks, sandwiching the students before letting them have it with their truncheons.

Sometimes the police met massed charges with water cannons (often spiked with eye irritants), but the narrow streets of typical Japanese cities often prevented that. Some water cannons sprayed dyed water so the rads at the forefront of the charges became clearly identifiable and arrestable.

These massed charges had the youngest students in the vanguard. Teenagers were mostly inexperienced, so readily accepted the risks that experienced protesters had learned to avoid. They'd act more aggressively in order to prove themselves. Plus - and this was the clincher - they weren't yet 20 years old. Under Japanese law they were minors, meaning they'd receive more leniency from the courts. They might be let off with having to issue an apology (Ha!) or with a warning (Ha ha!) or a small fine. Such fines could be paid by the group's emergency funds collected by the groups' most attractive female members soliciting donations at subway exits.

Say hello to my gebabô!

Testosterone drove these protests. All but the most ardent female radicals were limited to support roles far from the main action. During lulls in the protest cycle, "the girls" brewed the tea, solicited donations at subway exits, rolled bandages, emptied the ashtrays, made posters, distributed pamphlets, emptied more ashtrays......

Older, more experienced protesters usually got molotov-cocktail or rock-throwing assignments. As the police absorbed gebabô charges the radicals' rear-guard maintained a furious barrage of missiles and/or molotov cocktails. While dealing with massed charges and hand-to-hand fighting, the cops faced more fire and rocks (with some protesters hit by friendly fire). Teargas was the normal response if water cannons weren't available. On good days they could use both.

Demonstrations occasionally targeted individuals. President Eisenhower's Press Secretary's visit in 1960 met such violent protests that he feared for his life. An American military helicopter whisked him to safety. Some "attacks" were laughable. In Tokyo in 1969 a student radical penetrated the police cordon and tried to stab U.S. Secretary of State William Rogers with a sharp pencil. Rogers was unharmed. The attacker targeted the wrong guy.

The riot police were Japanese law-enforcement's elite, numbering 29,000 by 1969. Applicants passed rigorous psychological and physical tests before training intensively for urban warfare. Most were officially limited to only a few years as riot cops before reassignments to safer duties. This was to prevent burnout from the stress, the injuries and all the adrenaline.

It was an exciting, prestigious and well-paid part of their career, despite the constant criticism. The police always over-react, various media outlets and politicians would declare. Not at all, they're far too lenient, insisted others. The students are merely exercising their democratic rights, you fascist thugs, cried the Left. Crack more skulls and make more arrests! demanded the Right.

In any case, the riot police were not above raiding hospital wards after a street battle and beating injured radicals in their beds.

Nothing to see here

5. THE TOWER

Ask any Japanese person who remembers the Tokyo University (TôDai) Siege and you'll always get a reaction. The final assault by thousands of riot police on Japan's most prestigious university was televised nationwide. Many old-timers can still recall where they were and what they were doing when they heard the news. This was the protest movement's turning point.

It started in the spring of 1968 when senior medical students politely protested unwelcome changes to their training regimen. The annoyed administration's heavy-handed response forced a confrontation. Both sides dug in. The lukewarm support the students had received until then - these were medical students, after all - intensified. By July 1968 most of TôDai was on strike.

The administrators were trapped. The med students' demands were reasonable, but Tôdai couldn't lose face by backing down. The campus faced paralysis. Academic life was frozen. The entrance exams for the Spring 1969 intake were scrapped. One by one each department shut down. And about 20 other universities had "solidarity rebellions" supporting TôDai's protesters.

Meanwhile, "rads" occupied Yasuda Auditorium, the 9-story edifice dominating the campus. Riot police evicted them. The students then coordinated their resistance. And before you could say The Revolution starts here they'd retaken Yasuda Auditorium.

By the end of 1968 a partial accommodation was within reach. But the factions occupying Yasuda Auditorium started fighting each other as well as the police. They occasionally took time off from uchigeba to "arrest" professors and publicly interrogate them over blaring loudspeakers, just like the Red Guards in China's Cultural Revolution. One professor endured nine straight days of this.

It just kept escalating

The cops were in a bind. Order had to be restored. Yet unresolved legal questions about police jurisdiction and university autonomy muddied the waters. The administration faced censure for even involving the cops in the first place. But by now this had dragged on long enough, and something had to give. Tokyo University had become Tokyo Jungle.

In mid-January 1969 the media reported the police were preparing an all-out assault to dislodge the rads from Yasuda Auditorium. 8,500 police assembled. Students on nearby campuses tried to divert the police with impromptu riots. The cops ignored them and zeroed in on Tôdai.

All the various factions in the auditorium put uchigeba on temporary hold and coalesced against the common enemy. All except Kakumaru (white helmets with red stripes), which made a complete withdrawal so it could live to fight another day. (This added immeasurably to the hatred Chûkaku-ha - white helmets with the characters for "Central Core" - already bore its former ally.)

Confederates on the ground helped the holdouts stockpile molotov-cocktails, rocks, bottles of acid, bricks and whatever they could scrounge at short notice. They'd long ago rained all the desks, tables, bookshelves and doorknobs down on whoever was blaring demands that they put an end to this nonsense and come down this very instant. The final showdown loomed.

Actions: louder than words

The police had shields, clubs and 10,000 teargas grenades. They cut off the auditorium's water, gas and electricity. Helicopters dumped freezing water onto the students while enormous water cannons blasted the auditorium from below. Evening news reports televised ghostly images of the students hurling flaming bottles over the ramparts, creating arcs of sparks in the night sky.

On the second day red, waterlogged flags still adorned the tower. The police continued the water attacks from above and below. The students maintained their avalanche of bricks and molotov-cocktails. But the cops made headway, advancing floor by floor, squeezing the radicals into the building's top floor where escape was impossible.

On Day 3, as the non-stop nationwide TV coverage transfixed Japan, the students ran out of both missiles and options. A few flung their own shit at the police with improvised catapults. But despite their hopeless position they resolved to go down fighting. They grabbed their gebabô, soaked their anti-teargas towels in water - there was no shortage of that - and set themselves for the final onslaught.

Wave after overwhelming wave of elite cops raided the top floor. Vicious hand-to-hand fighting ensued. The police prevailed. What remained of Yasuda Auditorium reverted to university control.

This should do the trick

The police commander then made an astonishing gesture.

He later admitted he was not without sympathy for the students' grievances, but he'd had a job to do. He praised their courage and spirited determination.

That was why, when the last gebabô hit the floor and the last "rad" surrendered, he told his men to stand back.

Stand back, he ordered, and let them get cleaned up and sort themselves out. His panting, sweating, bleeding front-line cops - 650 of whom had sustaiined injuries - reluctantly obeyed. Those students who were still ambulatory assembled and linked arms. They then stood erect, gathered together with other faction members, linked arms and belted out rousing renditions of The Internationale. Hands on their heads, they marched proudly down the stairs - each according to his faction - to be handcuffed and stuffed into paddy wagons.

6. TIME WAITS FOR NO ONE

But 1969 brought changes. Public support waned. People muttered: Sure we disapprove of the Vietnam War. And sure we wish for Okinawa's rightful return. And sure we want Japan and Okinawa out from under Uncle Sam's thumb. But why all this chaos? All this disruption to everyday life for us ordinary folks? So much teargas and violence on the streets? Over 500 arrests a month in 1968! Anyway, aren't students sometimes supposed to, you know, study?

The more perceptive radicals sensed the decline. Apart from America agreeing to return Okinawa on absurdly lopsided terms, there was nothing to show for all their efforts. The Yankee war machine still attacked Vietnam from bases in Japan and Okinawa and capitalism was still firmly entrenched. The Revolution seemed as remote as ever. The movement had degenerated into a ritualistic slugfest between two boxers on autopilot. Greater public support was essential.

Public support? Perhaps the unions...? Sorry, kids. This isn't the 1950's.

Stirring newsreel images of French students and workers marching arm-in-arm served to reinforce the message: Japan's protest movement was stuck. The unions felt their interests no longer overlapped with those of the radicals. The urban proletariat lacked enthusiasm. The farmers cared more about soy beans than social issues. A few high school hotheads were keen, but so what?

More bad news: the police had informants in the movement. They weren't undercover cops. The nagging question became: When the cops secretly interrogate a rad then very kindly release him back into the movement, how can we be sure of his loyalty?

It was soon obvious that the police were blackmailing rads into becoming informants.

Police raids on radical hideouts suddenly sharpened. There were five simultaneous raids from Tokyo to Osaka on one September night in 1969, with 21 arrests. At the October 21st Anti-War Day protest the cops knew where the leaders would be even before some members of their own organizations knew.

More key arrests made, more dark suspicions raised.

Yet the police had their own looming problem. Those September raids netted not only key radicals, but chemicals. Chemicals for making explosives, said the lab reports. A collective groan filled the National Police Agency.

A new development had emerged. The recent increase in molotov-cocktail attacks on police stations signified a major change in tactics: some radicals were escalating from battling the riot police to hit-and-run fire-bomb attacks on selected targets. They were old hands with those molotov-cocktails. But were the rads now planning to bomb their way to victory?

THE REVOLUTION THAT ATE ITSELF: JAPAN'S RADICAL STUDENTS

(Part 2)

By the early 1970's Japan’s student protest movement became increasingly violent and morphed into something far more sinister.

I. BOMBS AND BUSTS

II. THERE’S REVOLUTION IN THE AIR

III. AN OFFSHOOT OF AN OFFSHOOT OF AN OFFSHOOT

IV. THE MERGER

V. THROWING OUT THE GARBAGE

VI. THE SNOW MURDERS

VII. NOW WE ARE FIVE…

VIII. …AGAINST A THOUSAND

IX. THE DANGLING THREADS

X. DREAMS OF ’68

I. BOMBS AND BUSTS

Bombs? asked Takaya Shiomi, dropping ashes from his cigarette. We’re absolutely going to use bombs!

That’s what the National Police Agency would’ve heard Shiomi declare in late 1969 if they’d been able to bug his conversations. This ex-philosophy major at Kyoto University founded the notorious Red Army Faction (RAF) that summer.

The RAF’s “parent” was the Communist League, known by its German nickname Bund ("Federation"). Bund was itself an offshoot of the mainstream Japan Communist Party.

You’re all talk and no action. We’re out of here! snarled Bund as they stormed out of the Communist Party in 1958. Which was what Shiomi’s people snarled when they stormed out of Bund in 1969.

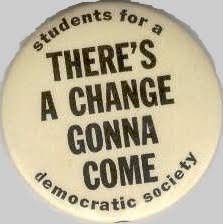

Action? Shiomi asked, dropping ashes from his cigarette. The Red Army Faction is all action! We’re an army, not like those Bund wankers. He challenged convention by forging alliances with other radical groups. He engineered mergers, always on his terms. He even attempted a trans-Pacific alliance with the American outfit Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), but his timing was off. And he foresaw a road paved with bombs leading to victory in the class war.

They changed to The Weathermen

Traditionalists deplored Shiomi’s ecumenism. Shiomi called them dinosaurs. Comrades! We all want to hasten the Revolution. It hasn’t started in Japan (yet). But it has in Cuba and China. If we’re shoulder to shoulder with them, we share their victories and bring the World Revolution closer. Right?

Next, he addressed the RAF’s demographics. We have too many university boys. Bring in the workers! And the women. But no philandering. Remember our mission: to detonate bombs and hasten the Revolution through armed struggle.

We’re soldiers, Shiomi reminded them, dropping ashes from his cigarette. Soldiers kill.

His followers with fire in their eyes loved that kind of talk. Soon the Red Army Faction had 150 core “soldiers” and hundreds of non-core supporters nationwide. Many were unusually young. So young that the RAF’s alpine bomb-assembly camp had a 15-year-old trainee. Eight were still in high school.

We know this because one or two youngsters simply had to tell a trusted friend: This is TOP TOP TOP SECRET so don’t breathe a word, but I’m going to Daibosatsutôge in early November to learn how to make bombs! Then some of us head to Tokyo and blow up the Prime Minister’s Residence! And start the World Revolution!

The police pounced and made 53 arrests.

Well, okay, said Shiomi, dropping ashes from his cigarette, let’s work on the next plan.

The RAF’s rank-and-file continued their bomb-assembly training. The senior members explored options. Meanwhile, most other radical groups stayed committed to charging the police lines and the tear gas, their gebabô held high. The RAF snorted derisively, like Flat Earthers watching a NASA documentary.

But Shiomi wasn’t destined to stay top dog. The cops nabbed him in March 1970. The arrest was a lucky fluke, a case of mistaken identity which played out beyond the cops’ wildest dreams. It came just days before his “next plan” was scheduled to take off.

II. THERE’S REVOLUTION IN THE AIR

Many years later, when Shiomi was an ex-convict working as a parking attendant, he described the Red Army Faction’s plan for Japan’s first hijacking as “a success which ended in failure”.

His nine-man team researched and rehearsed the hijacking of a Japan Airlines passenger jet. They planned to wear conservative clothes to avoid attracting attention. Two were the RAF’s most senior members. The youngest was 16 years old. One was the bass guitarist for Japan’s top psychedelic band, Les Rallizes Dénudés (a group whose name was intended to remain mysterious and unpronounceable to its fans).

They selected JL-351, a regular commercial flight from Tokyo to the southern city of Fukuoka, on March 31st. In this era before x-ray checks and metal detectors they easily smuggled on knives and pipe bombs. The seven crew members and the other 113 passengers suspected nothing.

At cruising altitude the hijackers brandished their weapons and demanded to be flown to North Korea. When the captain regained his composure he explained the plane couldn’t reach the North Korean capital – Pyongyang – without refueling in Fukuoka. The hijackers mentally winced. Their planning hadn’t considered this. But they had no choice.

At Fukuoka 300 police – some disguised as Japan Airlines staff – and airport officials surrounded the plane, buying time by claiming a stalled plane blocked the runway. They negotiated the passengers’ release, but 23 women, children and old people were all they could get. Then the stalled plane miraculously repaired itself and JL-351 took off for Pyongyang.

Free to flee

The plane landed 90 minutes later. As the elated hijackers prepared to disembark, their suspicions were aroused. Where were all the North Korean flags? And where were all the obligatory pictures of President Kim Il-Sung?

JL-351 had actually landed in Seoul.

At the subsequent official inquiry the crew testified their navigation directions had come from air traffic controllers claiming to be North Koreans. Only when they noticed all the incongruities did they discern they’d been deceived.

Japan’s Transportation Vice-Minister went to Seoul to take charge. He offered himself as a hostage in exchange for the remaining passengers. JL-351 had left Tokyo 79 hours earlier. Everyone was hungry, smelly and exhausted. They were out of cigarettes. The toilets overflowed. The hijackers agreed and the plane took off.

At Pyongyang Airport the North Koreans interrogated everyone separately. Then they provided showers, fresh clothes and a lavish banquet. They returned the plane, the crew and politician to Japan. Then the hijackers informed their hosts this hijacking was merely part of a much grander scheme to reach Havana, where they planned to partake of Cuba’s revolutionary experience and learn valuable lessons to be applied in Japan. So how soon, please, can you arrange to fly us there?

Current circumstances present difficulties in this regard, said the North Koreans. What they left unsaid was: You’re not going anywhere. What are we, your travel agents? The hijackers received apartments in Pyongyang. They twiddled their thumbs, convincing themselves they’d soon be in Cuba. But as the days became weeks and then months, reality hit.

They were ordered to study Korean and work as translators and language teachers. Later some young Japanese women were lured to Pyongyang and forced to marry them. And there most of them grew old.

"Long live the armed solidarity

of the Cuban and North Korean

peoples!" (Translation by Charles

M. Mueller)

III. AN OFFSHOOT OF AN OFFSHOOT OF AN OFFSHOOT

Shiomi’s successor had hardly taken over the RAF when detectives arrested him on his way to his fiancée’s apartment. (His fiancée later became one of Hiroko Nagata‘s “snow murder” victims.) In his pocket they found detailed plans to kidnap an ambassador and exchange him for Shiomi.

More arrests followed. The leadership now devolved onto Tsuneo Mori. A native of Osaka, he’d never had much luck. He missed out on the university of his choice. As a college student Mori adored a woman who was spreading around what he’d assumed was exclusively his. He became depressed and abandoned radicalism. He withdrew into himself. But a friend – one of the future hijackers – enticed him back into the radical fold.

As a leader Mori unnerved subordinates during conversations with his “loud silences”. He defied the current fashion and kept his hair short, like a warrior-monk. He knew Shiomi’s claim about the Red Army Faction being all action was hyperbolic. Its loose organization meant each decision was up for debate and review. Mori preferred things to be conclusive, just like when he captained his junior high school’s kendô (Japanese fencing) team.

Listen, said Mori, we need to tighten up. Security nowadays is a joke.

“Given your predecessor’s carelessness, we agree.”

All this international stuff gets us nowhere. Shiomi’s worldwide plans are pointless. We need to focus on Japan.

“We have no objection.”

We need to tighten up and make bombs to kill imperialists. And rob banks for money to buy guns and smash the system. Smash it right here in Japan.

“Not so fast!” said 25-year-old Fusako Shigenobu, the woman being arrested in Part 1’s second protest video.

She became "The Red Queen"

Shigenobu was the daughter of a one-time Kempaitei (Japanese "Gestapo") officer. The gossips claimed she worked as a hooker to raise money for the Radical Left. She’d actually worked part-time – among other jobs – for a soy sauce company and took university courses at night. In the testosterone world of left-wing extremism she really stood out. Not just for her beauty, but for her reluctance to “play a woman’s role” and for her passionate devotion to the Revolution. Shigenobu cared deeply about the Palestinian situation and took issue with this new leader’s direction.

Mori usually avoided direct contact with her. They spoke through messengers:

“Comrade Mori, the imperialists keep killing the Vietnamese and the Palestinians. So why don’t we kill the imperialists? Why do we target Japanese cops when the real enemies are in the Middle East and Vietnam?”

You want us to go to Vietnam!?

“No. I want to fight for our Palestinian comrades in the Middle East. And I’m sure other comrades will join me.”

Well, said Tsuneo Mori when other comrades joined her, off you go then! Mori loathed this vexing woman. He was thinking about bank robberies and guns. Let Comrade Shigenobu’s team play with their Arab chums in the desert. We have serious business right here.

There was a snag.

Shigenobu’s police record would derail her passport application. But in that pre-computer age if she changed her name by marriage and immediately applied for a passport she could leave Japan before the paperwork caught up. An RAF member married her and in early 1971 they all left for Lebanon.

Their airy concept of a Red Army Faction Middle Eastern branch didn’t survive contact with reality. How could they coordinate with Japan? By telegram? Shigenobu’s people were isolated in Lebanon. But that suited her, especially after hearing disturbing news from Japan that autumn of the RAF merging with a group she detested. (More on this in Part IV.) So The Red Queen – her nickname referred to her fashion sense as well as her radicalism – embedded her people with Palestinian groups, cutting all notional RAF connections. Later she renamed them the Japanese Red Army (JRA).

The proto-JRA sent shockwaves in May 1972 when three of its members flew to Israel’s Lod Airport on fake passports. They whipped out Czech rifles and opened fire indiscriminately, killing 26 people and wounding 80. One attacker was Shigenobu’s husband. He and another were killed. The third, Kozo Okamoto – a former agriculture student – was wounded as he attempted to blow up a plane and himself with a grenade. He faced an Israeli court. They learned his brother was one of the JL-351 hijackers. It must run in the family, they said.

Okamoto behaved outlandishly at his trial.

He wrote an official confession admitting total guilt but signed it with a false name. He claimed he’d converted to Christianity. When his lawyer noted some uncertainty as to his client’s age which – with Okamoto’s youthful features – might suggest he was a minor, Okamoto immediately told the court he was 24. And he attempted a do-it-yourself circumcision in his prison cell using nail clippers.

Okamoto & Shigenobu '72

Okamoto walked free in a prisoner exchange 13 years later. He bounced around the Islamic world then settled in Lebanon.

The Red Queen stayed put, engineering this hijacking and that embassy attack. She had a daughter, Mei (from the Japanese word kakumei, “revolution”), wrote books and granted interviews to Japanese journalists. Then she surreptitiously entered Japan after three decades among the Palestinians. But her cover was blown. In prison she was diagnosed with cancer, and was released in May 2022.

IV. THE MERGER

Meanwhile, Tsuneo Mori turned the shrinking Red Army Faction into bank robbers. “Combat platoons” studied locations, security systems and getaways. Things prospered until their six-million-yen armed robbery. That one really stood out. Not only for the haul but for the information it provided the cops.

Following every lead, they made arrests and recovered the money. But how, they asked, did a shotgun from a recent gunshop robbery committed by Hiroko Nagata‘s group, Keihin Ampo Kyoto (Tokyo-Yokohama Joint Struggle Group) get into RAF hands? Collaboration?

More than that. Mori’s crew had money but few weapons. Nagata’s group had guns but no money. The RAF’s swerve from worldwide revolution to eradicating Japanese capitalism overlapped with Nagata‘s group's principles. A merger would be mutually advantageous. So a merger was made.

Mori (26) and Nagata (27) were officially co-leaders. Hiroko Nagata downplayed her femininity. She comported herself as a revolutionary first, a woman second.

Nagata later told her police interrogators she was “a very sensitive person” whose move from studying pharmacology to embracing terrorism resulted from her “interest in society and how a person should live”. Never popular with the opposite sex, she was self-conscious about her looks. She had Graves’ Disease, causing her eyes to bulge and her voice to deepen. Nagata detested hot weather – another Graves’ symptom – and became irritable in the summer. She spurned cosmetics. “Being pretty,” she told her female followers, “just leads to bourgeois sentiments.”

She was the common-law wife of another member (who was already married with a baby), but there was little warmth there. We’ll hear about him later. Towards the end she announced she was “divorcing” him to “marry” Tsueno Mori, who also had a wife and baby. Nagata’s police interrogators showed a prurient interest in her dealings with men. They asked about a prison visit she’d made in late 1969 to a recently arrested radical. Why had she spoken so harshly to him? She said he’d once been her mentor in the gritty world of radical activism but had raped her earlier that year while his wife was away.

Now, in mid-1971, Nagata merged her group with the Red Army Faction. This official union’s new name was the United Red Army (URA). She could bring valuable energy to the group after all the arrests and departures. The RAF’s former alpha female was off in the sand dunes with the Palestinians, but here was a new one. Strong like a man, and with leadership experience. Nagata would fit right in.

But first she had some unfinished business.

V. THROWING OUT THE GARBAGE

Hiroko Nagata hated deserters from The Revolution. Such human scum deserved death. In August 1971 she told Mori she planned to “take care of” two people who’d fled Keihin.

They were a nursing student and her clueless ex-boyfriend. Nagata’s guys kidnapped the woman, beat her senseless then strangled her. Earlier the ex-boyfriend had foolishly spoken of one day writing about his experiences with Keihin. A URA woman lured him into a trap. Nagata’s guys strangled and buried him near his ex-girlfriend.

These murders unsettled Mori. Not that he was squeamish about these matters. He’d once given such an order himself, but the guys he’d sent to kill a deserter showed weakness and spared her. Yet he noticed Nagata’s people always obeyed her orders to the letter. Mori sensed this made him look weak. His leadership may be imperiled. He needed to reassert his authority. This got him thinking.

Tsuneo Mori: warrior monk

Mori realized the URA’s unity was illusory. The ex-Keihin and the ex-RAF members rarely mingled. There were regional and social differences. You could tell by their accents. Unlike the RAF, Keihin had recruited many women. It marched to a different tune. He now decided to reinforce the group’s solidarity and ideological purity.

In late 1971 he ordered a temporary stop to the bombings of police stations. The URA would now enter a period of intense physical training, self-examination and stringent ideological preparation for the revolutionary struggle.

And he would cull the weakest members.

VI. THE SNOW MURDERS

Mori rented an isolated cabin in the mountains. Attrition had reduced the URA to 19 men and 10 women. If there’d been any comedians in their ranks they would have thought – but never uttered – We’re now the United Red Platoon.

It was the dead of winter. Overnight temperatures plunged to minus 20° Celsius. Mori had everyone (except a pregnant woman) run through the snow, hide behind rocks, scramble up hills, roll down hills, lob imaginary grenades and shoot imaginary cops while chanting revolutionary slogans and issuing bloodcurdling cries. They lived like Spartans, eating simple food and sleeping on the floor. There was only one wood-burning heater and no electricity or running water.

The rules were simple: no alcohol and no philandering. When they weren’t rehearsing the Revolution outdoors they were inside the cabin reading turgid revolutionary tracts under kerosene lamps.

Every day they underwent sôkatsu: self-criticism, confession and discussion. The purpose was ideological purification. Mori dictated the tone of these cultish sôkatsu sessions, but he artfully made the required terminology so vague that nobody was sure what they were confessing to or what constituted valid criticism. Anything could mean anything. Every sentence became a minefield. It was like playing a game whose rules were known only to the umpire.

Say the wrong thing – but how did you know it was wrong? – and you’d be the target of a Mori tongue-lashing or Nagata’s kicks and slaps. The first fatality was a 21-year-old male named Mitsuo Ozaki. His revolutionary zeal had been deemed insufficient. His punishment was to be “toughened up” by having a much stronger man beat him. Ozaki took the blows, then thanked Mori for the chance to improve himself. Mori interpreted this as bourgeois ingratiation and a sign of weakness. He ordered Ozaki to stand upright all night.

The next day – New Year’s Day 1972 – they beat him again then tied him to a post in the snow. Mori interrogated him and declared him still unworthy of URA membership. He needed another beating. That was the coup de grâce. Ozaki bit off his tongue as he expired.

This shocked the group. They’d only wanted to reform Ozaki, toughen him up, not kill him. The silver-tongued Mori absolved them, saying this was nobody’s fault. Ozaki brought death on himself by not measuring up to the required revolutionary standards. This was death by defeatism.

Nagata overheard one guy’s “inappropriate conversation” with a female member. He’d be the next fatality. She demanded his beating as a warning to the other males. The warning resulted in six broken ribs and a ruptured liver.

Kazuko Kojima was accused of having once divulged information to the police. Mori made her and a 22-year-old male Yoshitaka Katô (who’d murdered the deserters the previous summer) write self-critical essays. Late that night Kojima complained Katô was molesting her. Nagata decreed punishment for both: Katô for his alleged molestation and Kojima for providing temptation by sleeping nearby.

Katô’s two teenage brothers were ordered to beat him. They tied him and Kojima to posts outside the cabin. Katô repeatedly banged his own head on the post, claiming this would produce a stronger revolutionary mindset. But that revolutionary mindset never came: he and Kojima died of exposure.

And so it went, one pointless death after another. Nagata targeted Mieko Tôyama, the ex-fiancée of the RAF leader – Mori’s predecessor – who was arrested near her apartment in 1970. Nagata hated how Tôyama wore a ring and had blithely brushed her hair during a meeting. She accused Tôyama of sexual misconduct “while on duty” with Masatoki Namekata, a TôDai siege veteran. Nagata made Tôyama punch herself in the face for 30 minutes.

Namekata watched all this then broke down and confessed to having contemplated desertion. They broke his legs and tied him and Tôyama to posts in the snow, where they both froze to death.

And so it went. It was now mid-January 1972. The group lynched one guy for confessing to sexual urges. Another was lynched for not participating wholeheartedly in a previous lynching. Another committed suicide by deliberately angering Mori, then demanding immediate execution. The 8-month-pregnant woman, a 24-year-old Keihin veteran, was the URA’s cook, cleaner and treasurer. Mori suspected she had ideas above her station, so she was the next to go. They discussed inducing her baby’s birth and raising it as a United Red Army child. But mother and baby died after her beating. Her husband was among her killers.

During all this some members braved the elements and escaped. The URA continued tearing itself apart. You protected yourself by attacking someone else. Find a reason, any reason. Beating or stabbing someone helped you vent your frustration and forget the secret fear that you might be the next one to get it.

Tissues inside a sleeping bag proved that one guy had masturbated. He was the next one to die. And so it went.

They didn't make the cut

Hiroko Nagata’s putative husband’s loyalty had ensured his survival through this sôkatsu process. He was Hiroshi Sakaguchi. One mid-February morning Mori and Nagata left for a few days "on business" (which no doubt included comfortable accommodation). Before leaving they summoned Sakaguchi – No hard feelings about the “divorce”, comrade! – and ordered him to take charge of the URA’s remnants in their absence.

Later that day Sakaguchi sensed the noose was tightening. He learned local people had reported a suspicious group of young city slickers – some with distinctive Osaka accents – in the area. Time to abandon the cabin and move to a nearby cave. He contacted Mori and Nagata at a pre-arranged phone number about this. Then everything went awry.

VII. NOW WE ARE FIVE…

Sakaguchi’s people headed for the nearby cave. A discovered newspaper article revealed their cabin had just been raided. He decided the cave was now too risky and they needed a safer hideout further away. But he couldn’t notify Mori and Nagata, who still thought the cave was everybody’s destination.

On February 17th Mori and Nagata drove to the cave but encountered a policeman at a checkpoint. Mori smoothly explained he and the lady were part of a film crew scouting remote locations. The cop said, "This area’s off-limits. You’ll need to find an alternative route." The couple pretended to drive off, then returned to the area attempting to link up with Sakaguchi’s group, still unaware of the change in plan.

The same policeman from the checkpoint noticed their return and became suspicious. He called for backup. They cornered the couple. Nagata drew a knife and – being a “she-devil” – lunged at the nearest cop. Mori put up weak resistance. When the police found they’d nabbed the URA’s leaders they couldn’t believe their luck.

Hiroshi Sakaguchi was now the United Red Army’s leader. He just didn’t know it yet. Survival was now the sole concern. A group of nine was far too conspicuous. He ordered four of them to somehow escape independently. He would take a separate route with the remaining four.

After hasty goodbyes the first group trudged off through the snow. By morning they reached a local train station. A newsstand owner called the police: There are two men and two women on the platform. They look raggedy and suspicious. One member approached her to buy newspapers and cigarettes. The cops swooped and arrested them.

VIII. …AGAINST A THOUSAND

The United Red Army was now Hiroshi Sakaguchi (25); Kunio Bando (25), a veteran RAF footsoldier; Yoshio Masakuni (26), a Keihin stalwart; and two teenagers, the surviving Katô brothers (whose oldest brother they'd helped beat to death) .

They found an isolated cottage. But a police helicopter spotted them. After a brief firefight they escaped and reached a three-story concrete tourist lodge called Asama Sanso built into a rugged mountainside. Here they’d make their do-or-die stand. It was February 19th, 1972.

The owner’s 31-year-old wife was alone. The URA stormed in, tied her up and checked every room in case she had company. They blocked every window and door with furniture, bedding, whatever they could find. They had food for about 10 days, a TV, a radio, four shotguns, a rifle, a revolver and abundant ammunition.

The police surrounded the lodge and deployed snipers. But then Tokyo sent orders: Do nothing to endanger the hostage. Take the radicals alive repeat alive. Down came the snipers. Cops lined every approach to the lodge. They kept the electricity, gas and water connected in case the hostage was still alive.

Two days later the police probed for weaknesses. The URA opened fire, injuring two officers. By February 22nd there were 1,200 cops at the scene. Hundreds of TV-crews, reporters and photographers jostled for advantage. The cops brought two of the rads’ mothers to beg them over loudspeakers to surrender. No response.

This may take some time

Media helicopters buzzed overhead. Unwanted advice poured in from politicians and media pundits. The police faced a host of unknowns:

* Was the hostage alive?

* How many rads were there?

* What shape were they in?

* What was their ammunition supply?

* Did they have explosives?

* Would they commit suicide and kill their hostage rather than face capture?

One local resident attempted a solo rescue effort, which cost him his life. The hostage, Yasuko Muta, usually remained tied up. After her rescue she strongly denied being mistreated. She testified the radicals explained leftist political ideology to her. One gave her a Buddhist charm, assuring her it would keep her safe.

During a lull the URA watched the news and saw President Nixon visiting China. Their world now seemed upside down.

The cops cut the electricity. The next afternoon they demanded proof the hostage was unharmed. No response. At nightfall they attacked with tear gas and smoke bombs but withdrew under heavy fire.

The police tried new tactics. They played taped noises of sirens, screams, motor cycles and chainsaws at excruciating volume. Sleep became impossible. That was the point. In the morning they threw smoke bombs at the lodge to cover their advance. But the fickle mountain winds dissipated the smoke and they withdrew again. Then they deployed three high-pressure water cannons, the type used at Yasuda Auditorium in 1969.

The water cascaded into the lodge. The police followed up with tear gas. They sprayed more water, hoping the freezing temperatures would ice up the lodge and make it uninhabitable. A dense fog rolled in. They brought in high-powered searchlights. They set up a field hospital in preparation. NHK, the state TV network, reported a 90% viewer share for its round-the-clock coverage.

On Day 10 (February 28th) the cops stretched anti-grenade nets outside the lodge. They appealed one last time for the rads to give themselves up. Gunfire was the reply. Then they brought up a crane swinging a huge metal ball to shatter the walls.

The crane smashed gaping holes and the water cannons restarted. An elite assault unit entered the lodge. Downstairs was clear. The unit took fire from above. One round killed the officer directing the assault. The URA and the hostage were upstairs. A bomb exploded downstairs, injuring several policemen.

Tokyo sent new orders: Disregard previous orders to take the radicals alive. Shoot to kill. But by now the radicals and their hostage were cornered on the lodge’s top floor. There was no escape. Like the Tokyo University rebels two years earlier they saw the jig was up and surrendered. Mrs. Muta still breathed. And the United Red Army was history.

IX. THE DANGLING THREADS

Tsuneo Mori and Hiroko Nagata kept their mouths shut at first. But the others blabbed to the cops.

The police dismissed their stories of 12 murders in the cabin.They’d seen evidence of violence at the abandoned cabin. But murder? Killing policemen we can believe. And killing rads from rival factions and innocent civilians. But killing 12 of your own? Your sick, grotesque stories are just foolish attempts to waste our time and lead us astray. But they discovered every name, date and grave location checked out. The remains were all there, waiting to be found.

The media descended and the feeding frenzy began. Every reporter and talking head feasted on the lurid details. Everybody had an opinion why these middle-class university students became mindless killers. Bad parenting. Extreme stress. Weak morals. Excessive discipline. Insufficient discipline.

Another one here

Later analysts compared how Japan’s media and judiciary had treated Mori and how they’d dealt with Nagata. Mori was viewed as a sadly misguided fellow. His actions were horrifying but motivated by a discernible political ideology. So it was somehow possible to make sense of his actions But the court of public opinion judged Hiroko Nagata differently. She was a sadistic witch, a crazed hag. Severe character defects fueled her abominable deeds. There was talk of hormonal problems.

Nagata wrote a book in prison. Sixteen Grave Markers: Youth of Fire and Death expressed remorse for her deeds. A prominent Buddhist nun became her regular visitor and friend. Nagata died of brain cancer just before her 66th birthday, after nearly three decades on death row. The courts had rejected her lawyers’ every appeal.

Tsuneo Mori committed suicide on January 1st, 1973. He wrote a poem then hanged himself in his cell.

Hiroshi Sakaguchi, the United Red Army’s last leader, had a chance at freedom in 1975. The Japanese Red Army – Fusako Shigenobu’s crew in the Middle East – captured American and Swedish diplomatic posts in Malaysia. Sakaguchi was among the prisoners whose freedom they demanded. But he refused. He despised the JRA as deserters, and declared he’d continue fighting imperialism from his prison cell. Good luck with that, said the JRA, and scratched him from the list.

Kunio Bando, his ex-accomplice, was also on the JRA’s list. He eagerly grabbed the offer. Soon after his release he hijacked a Japan Airlines plane in Bangladesh. He’s still at large.

Takaya Shiomi, the Red Army Faction’s founder, wrote an apologetic memoir while serving 20 years in prison. After his release he laid low but later ran for office in a local election in 2015, finishing 22nd out of 23 candidates with about 300 votes.

In North Korea some hijackers died natural deaths. But two died trying to escape. Their deaths were officially industrial accidents, although how two translators got crushed by forklifts was never explained.

The North Koreans “gave” them wives (Japanese women lured to Pyongyang). In the 1980’s some of the wives were allegedly sent to seduce and kidnap Japanese nationals in Europe and spirit them to North Korea for nefarious purposes. A few wives are reliably reported to have returned to Japan, although the details remain stubbornly obscure.

One hijacker somehow spirited himself into Japan in 1985 and was soon arrested. But legal loopholes helped him out. He was a minor when he'd participated in the hijacking, plus there was no law against hijacking in 1970. So he did time on only a few minor charges. Another was nabbed carrying counterfeit dollars in Thailand in 2000. They transferred him to Japan, where he later died in prison.

And finally, most student radicals with “light” criminal records eventually felt the urge to straighten up and fly right. Many landed straight jobs in corporations and even the civil service. But those who were “well known to the police” – radicals with the longest rap sheets – faced shadowy futures on society’s fringes.

Surviving hijackers (Pyongyang 2014)

X. DREAMS OF ’68

Q: So why did Japan’s radical protest movement start?

A: The Left’s pre-1960 successes faded. For all its passion about liberating “the people” from capitalism, it was too weak to shake things up in any meaningful way. That’s oversimplifying it, but the mainstream Left was simply ineffective at sociopolitical change.

Q: So dissatisfaction with the mainstream Left spawned radicalism?

A: The students rejected the JCP’s outdated, doctrinaire, Moscow-dominated orthodoxy. They wanted to force “the people” to rise up and embrace revolution. By the 1960’s the social conditions were ripe: baby boomers crowding woefully inadequate universities, emerging youth culture, disgust at Japan’s cooperation with the Yankee war machine, rampant corporate and political corruption. Rebellion was in the very air.

Those were restive times – worldwide, of course – but Japanese youth had precious few ways to release their pent up anger. Violent protest was the surest way of putting their grievances out there.

Many radicals viewed things thus: doing nothing was tantamount to compliance.

One told a contemporary researcher: All we want is the battle itself. But there’s also this evocative quote from another book: a TôDai activist told one author in 1970: I feel solidarity with anyone who actually struggles hard to do something. That was it, you see: struggling hard to do something.

Q: But Western students struggled hard to do something too.

A: True. But consider the contrasts between Japanese and Western protests. Violence and mass arrests were normal in Japan. They were expected. And remember how many Western protesters carried placards and flowers? Japanese protesters carried gebabô and molotov cocktails.

And, unlike the West, Japan’s popular music scene had absolutely no sociopolitical dimension. There was no widespread counterculture such as in the West: a counterculture which ignored or subverted societal norms. A short-lived Japanese protest music fad emerged, but the all-powerful record companies and radio stations steered clear.

Keep in mind, too, drug use was expected among American radicals. It was practically unknown among Japanese radicals.

Remember the Red Army Faction’s plan to forge links with Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) in America? At that time some SDS renegades became the Weathermen (later the Weather Underground) and committed to a wave of bombings. They declared: Freaks are revolutionaries and revolutionaries are freaks. Around 1970 “freaks” wasn’t used pejoratively, but referred to long-haired people who embraced the counterculture, wore hippie clothes, got high and so on.

In the West beads, beards, bongs, bell-bottoms and the two-fingered peace sign helped proclaim The Revolution. But none of that applied among Japanese radicals, who rejected such epiphenomena as trivial and irrelevant. Keep singing Give Peace a Chance? You’re joking. And the concept of flower power – had they been aware of it – would have baffled them.

Q: But Japanese campuses weren’t all radicalized. Didn’t most students avoid radicalism?

A: Whenever normal academic activity essentially ceased, the nonpori (nonpolitical students) wanting to focus on their courses were officially told to “study at home until further notice.” Inevitably, on many campuses, you’d see only lots of activists doing their thing. This fostered the image that all Japanese students were radicals.

Campuses had right-wing groups too. They were less conspicuous, but aggressive. Nihon University‘s right-wing president encouraged his rightists to “get the Reds”. They were mostly ultra-nationalists and jocks. Their baseball bats and wooden kendô swords came in handy.

Q: How big was the protest movement?

A: There are various metrics. In ’68 about 80% of campuses had “some sort of conflict”, from mere sitdown strikes and lecture-boycotts right up to the Tokyo University siege and the ferocious, prolonged Nihon University “civil war” (which was every bit as brutal, and a story in itself). In 1969 dozens of university presidents resigned to take responsibility for all the disruption.

In ’68-’69 about 70 universities were barricaded, meaning the students effectively took over the campuses. 62 high schools were barricaded in 1969, and the police detained about 600 teenagers. By then the average monthly radical-arrest rate exceeded 1,000. Two cops died in on-campus “disturbances”, and 10,000 were injured in ’69-’70. There were over 100 bombings between 1969 and 1971. But that number excludes those incidents which – to save face – must have been hushed up or were reported as something less serious. And, of course, some bombs simply fizzled.

Q: Ultimately, though, little was achieved from all this. Why?

A: Having so many factions with competing priorities was decidedly unhelpful. In a nutshell, the radicals talked like political philosophers but acted like motorcycle gangs. “The people” they claimed to represent were appalled.

Remember uchigeba? Conflict between factions. One uchigeba incident epitomizes the factions’ “tribal warfare”. In Yasuda Auditorium shortly before the final assault in the Tôdai Siege, rival radical factions fought an all-out brawl. Nothing unusual about that, except that this was a three-way brawl. Three factions violently attacked each other simultaneously with gebabô and metal pipes.

How did they expect to unite “the people”? They couldn’t even unite themselves.

If the protest movement hoped to replace the existing order with the rule of the proletariat (“the people”) it needed that proletariat – the general working class – on its side. But that was impossible while the movement foolishly clung to its tribal loyalties. Its brutal factionalism alienated Japanese society. That endless internecine violence kept the revolutionary movement stuck in a hole.

The factions cared more about wiping each other out than working towards their common revolutionary goal. That really tells you something about their leaders’ tunnel vision. They were hopelessly blinkered. Their divisive tribalism contrasted starkly with the American anti-war movement’s – and the Paris ’68 movement’s – we’re-all-in-this-together approach. The Japanese had a shocking inability – or unwillingness – to see the big picture and act accordingly.

And the last straw was the United Red Army’s gruesome self-destruction. The movement could never win public support after that. People wondered: So that’s how they’d have us live? Facing death for brushing your hair, like Mieko Tôyama in that mountain cabin?

There’s one more thing. They were blind to the future. The activists were unanimous about “the people” needing a revolution now. But their post-revolution vision was hopelessly vague. So “the people” saw no reason to buy into any of that.

Q: What’s transpired since 1972?

A: That year the movement seemed to crash. Yet we can’t pretend that 1972 was the end of the story, even though the nationwide revulsion at the URA’s killing spree drained whatever impetus Japan’s Radical Left still had. That year the campuses quietened down and the violent mass demonstrations dwindled. But their uchigeba became homicidal.

During the mid-1970’s the vicious antagonism between two radical factions – the savage Chûkaku-ha and its ex-ally, the more self-disciplined Kakumaru – went haywire. Both sides ignored the class struggle and The Revolution. They just battled each other with deadly force.

They acted like Latin American drug cartels in a turf war.

Neither group lost sleep over collateral damage. You can imagine the public’s reaction to all that. Then, by the late 70’s, they turned from trying to exterminate each other to ignoring each other.

Kakumaru eventually went legit, enmeshing itself with the railway unions. Chûkaku-ha aimed to disrupt daily life. In the 1980’s it made some expertly coordinated and headline-grabbing – but pointless – attacks on infrastructure, government buildings and even an attempt to lob mortar shells at a G7 Summit. But by now its arson attacks had become a major irritant. What was the point? Why did it still even exist?

And like the other radical groups which still had a pulse, both outfits shrunk as their demographics changed. The new generation of students were indifferent. Fewer and fewer people – closer to middle age than their teens – pressed on.

Operation Diamond

We should also mention the Narita Airport expansion project (Sanrizuka) becoming the focus of the radicals’ remnants during the late 1970’s into the 1980’s. The government’s ruthless appropriation of farmland for the project backfired by presenting the Extreme Left – with Chûkaku-ha in the vanguard – with a neat package of grievances: rampant capitalism, exploitation of the masses, corrupt politicians colluding with rapacious developers, suppression of dissent, farmers violently dispossessed of their land, you name it. That dragged on for years and years.

Finally, one group from the mid-1970’s deserves a mention: the East Asian Anti-Japanese Armed Front (EAAJAF). It made the self-hating claim that Japan is an inherently imperialistic and wicked nation whose economy - and very survival - was based on exploitation. Its institutions were corrupt to the core and shamelessly racist. The root of Japan’s evil was Japaneseness. They declared Japan had a sickness in its heart. It had to be made to atone for its sins. Maybe even wiped from the map.

Its members minimized suspicion by living straight lives with straight jobs, financing themselves with their salaries, operating in three tiny, loosely connected “cells” called Wolf, Scorpion and Fangs of the Earth. Their secret codename for EAAJAF was, of all things, Clint Eastwood.

Unlike groups such as the United Red Army, its members maintained their established social and family ties, always keeping their anti-Japan activities - as well as their cyanide tablets in case of capture - totally secret. They swore to abstain from alcohol but were also free to leave the group at any time.

In 1974-75 they planted 11 time-bombs in various corporate headquarters. Their first time-bomb (Operation Diamond) destroyed the Tokyo HQ of Mitsubishi Heavy Industries. EAAJAF claimed Mitsubishi was a pillar of imperialism, as evidenced by the corporation’s defiant lack of public remorse over its use of Chinese and Korean slaves during the war. The explosion killed 8 people and injured almost 400.

One of EAAJAF's goals was to foment uprisings among the oppressed Ainu indigenous minority in Hokkaido and the native Okinawans. (This idea went nowhere.) They even tried – but failed at the last moment – to assassinate the emperor (Operation Rainbow).

Their ultra-secretive nature and hatred for their society gave them a particularly sinister image. Dogged police work and EAAJAF’s inability to completely cover its tracks eventually led to its demise. Unlike most other contemporary radical groups, as prisoners they freely confessed during interrogation. And their leader made public apologies.

Q: Getting back to the URA slaughter, what are your personal thoughts?

A: The media attention was indeed sensationalistic. It portrayed Mori as less culpable than “the she-devil” who partnered him. Mori had a political agenda, after all. But he had his own psychological baggage. He felt insecure, unable to live down his earlier withdrawal from the Red Army Faction after his failed romance. And before the 1971 merger he faced furtive, lingering insinuations that he lacked the balls for revolutionary leadership. Remember, at their arrest Nagata fought their captors but Mori's resistance was feeble.

Did these insecurities contribute to Mori’s excesses in the mountain cabin? Probably. But he was uncommunicative in custody – like so many arrested radicals – and he killed himself before they could probe this.

Q: What’s happening currently?

A: Those groups surviving today have become organizations with phone numbers, bank accounts and sometimes websites. Many are now straightforward lobby groups, campaigning for the working class. They’re still under routine police surveillance, but remain mere shadows of their former selves.

A more recent development provides a convenient finale to all this. You’ll recall the American occupation of Okinawa was a perennial grievance. Japan regained Okinawa in 1972, but before this the government accepted such a lopsided deal from Washington that 1971 became Japan’s “incendiary year,” a year of wild, savage protests.

In a November 1971 demonstration in Tokyo Chûkaku-ha activists (who else?) burned a young cop to death. The police vigorously pursued their prime suspect Masaaki Ôsaka (born 1950). He was on the run for almost 46 years, never leaving Japan.

They arrested him in Hiroshima in 2017. He’d been protected and supported by Chûkaku-ha supporters who’d stayed just below the police radar for decades. They’re now in the autumn of their lives. The police are following this up, but not just because these people aided a notorious cop-killer. The money required to keep Ôsaka healthy and safe for so long has attracted their interest. Was it stolen money?

In any case, those old-time radicals’ heyday was so very long ago. It was a different world back then. They’re living fossils now.

Q: What do they do these days?

A: We can imagine them gathering from time to time in somebody’s apartment (never the same apartment twice in a row, for security). They’re complaining about their arthritis, dropping ashes from their cigarettes, yearning for The Revolution, comparing battle scars, reminiscing about their best molotov-cocktails, their best gebabô whacks, their best adrenaline rushes and the tingling of their senses and how alive they all felt when it was the late 1960’s and they were all so young and anything was possible.

We owned the night

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Hiroko Nagata: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hiroko_Nagata

Tsuneo Mori: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tsuneo_Mori

Fusako Shigenobu: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fusako_Shigenobu

Masaaki Osaka: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Masaaki_Osaka

Kozo Okamoto: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/K%C5%8Dz%C5%8D_Okamoto

The hijacking: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Japan_Airlines_Flight_351

The URA's last stand:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Asama-Sans%C5%8D_incident

East Asia Anti-Japan Armed Front: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/East_Asia_Anti-Japan_Armed_Front

==============================================================================

RETURN TO MAIN MENU: http://www.sla.ne.jp/manfacingnortheast/

THE MEN WHO WEREN'T THERE: BUTCH CASSIDY & THE SUNDANCE KID: http://www.sla.ne.jp/manfacingnortheast/index.php?id=the-men-who-werent-there-butch-cassidy-the-sundance-kid

SHORTER FICTION: http://www.sla.ne.jp/manfacingnortheast/index.php?id=original-fiction-1

NEOLOGISMS (WORDS FOR WHEN THERE ARE NO WORDS): http://www.sla.ne.jp/manfacingnortheast/index.php?id=neologisms

THE LATIN LOVER (SHORT STORY): http://www.sla.ne.jp/manfacingnortheast/index.php?id=the-latin-lover

MOJO MAN: LIFE'S A HIJACK (THE STRANGE TALE OF ROGER HOLDER): http://www.sla.ne.jp/manfacingnortheast/index.php?id=mojo-man-lifes-a-hijack-the-strange-tale-of-roger-holder

MOVIES & SPOKEN WORD: http://www.sla.ne.jp/manfacingnortheast/index.php?id=movies

TWO SHORT STORIES: http://www.sla.ne.jp/manfacingnortheast/index.php?id=two-short-stories